Research Areas and Projects

Philosophical Characterization of Technology

I. Two Views of Technology

II. Existing Theories

III. The Triple Characterization

IV. The Cultural Quadrants

The Philosophical Characterization of Technology

I. Two Views of Technology: the Engineering View and the Humanities View

A. Thinking through technology with Mitcham

Mitcham's book Thinking Through Technology may look like a historical survey of philosophy of technology at first glance, but since it's a very young field the book actually provides a framework for the current study. Unlike in science or technology, where a new theory or invention often eliminates the significance of previous ones, many ancient philosophical thoughts are still alive today. The case is even more so in philosophy of technology. Traditionally technology was just regarded as an instrument associated with certain utilities. With the emergence of the dominance of technology in the modern world, technology gained substantially increased attention. That's when the systematic philosophical reflection on it began. As that happened only recently, in the 19th century after the Industrial Revolution, all previous philosophical thoughts of technology are still relevant for the moment.

Three major contributions of Mitcham's book are: First, it highlights the two contrasting views of technology - the engineering view and the humanities view. Second, it proposes a general framework for sorting out various thoughts in the field. Third, it applies the framework elegantly to the three typical Western attitudes toward technology. What follows is some elaboration and interpretation of these contributions.

- The engineering view

- Kapp Ernst Kapp's Grundlinien einer Philosophie der Technik (1877) was the first book ever to use the phrase "philosophy of technology" and have philosophy of technology as its central subject. His basic idea was that technology was the projections of human organs. This looked obvious, but had much more depth than common sense instrumentalism.

- Engelmeier The focus of Peter Engelmeier's philosophy of technology was on the social impact of technology. The impact was mainly manifested in economy, ethics and politics.

- Dessauer The emphasis of Friedrich Dessauer's philosophy of technology was yet another important aspect of technology: creation. In contrast to Kant he argued that technical creation provided a way to establish contact with things-in-themselves.

- Bunge Mario Bunge's idea represented an extremely optimistic view of technology. Influenced by logical empiricism he advocated to explain everything in scientific-technological terms. For him technology didn't only apply to material life, but also social affairs. Social engineering or even technocracy were obvious implications.

- The humanities view

- Mumford Lewis Mumford distinguished between two basic kinds of technology: polytechnics and monotechnics. Modern technology is a typical monotechnics, whose primary goals are economical expansion, political influence and military superiority, generally power. In contrast, polytechnics aims at aspirations of life and realization of diverse human potentials. Modern technology is not bad by itself, but there are more important things beyond it. We should put a limit on its unqualified expansion.

- Ortega For José Ortega y Gasset technics as an activity of creation is an essential part of human nature. In a sense it defines human existence. However, the irony of modern technology is that, as the highest stage of technics evolution it's drying up creative imagination, due to the adoption of scientific method.

- Heidegger Martin Heidegger also lifted modern technology to the level of ontology. To him modern technology defines people's way of being-in-the-world in the modern age. In particular, it takes the form of Ge-stell, in which nature is challenged, ordered, and treated as a reserve to satisfy people's insatiable desires. In this ontological existence most meaning of traditional life is lost.

- Ellul Jacques Ellul took a sociological approach to modern technology. The word he used, "la technique," not only referred to technologies in the material world, but also similar mechanisms and procedures adopted in various social areas, economy, politics, even culture. The primary feature of la technique is its autonomy. Its predominant objective is efficiency. Like Heidegger he also lamented the loss of meaning in traditional life.

- The four facets of technology

- Technology as object Obviously each technology has to be implemented in certain objects, otherwise its function cannot be realized. A closely related debate concerns the nature of artifact. My personal understanding is that the primary meaning of artifact is man-made tangible object. In this sense we have to clearly distinguish technological objects from artifacts. Some technological objects are not artifacts, because they are not tangible. Computer software is a good example. On the other hand, some artifacts are not technological objects, because they are not created with intended technical function. Art works belong to this category.

- Technology as knowledge What's at issue here is the difference between scientific and technological knowledge. It's not simply a know-what vs. know-how distinction. Technology also involves know-what. It's rather a distinction of know-why vs. know-how. The focus of science is to make sense of the what, whereas that of technology is how to realize a certain function. It could put why it works aside. So scientific knowledge involves theories with more or less universality. Technological knowledge also includes maxims and rules.

- Technology as Activity Technological activity includes both the creation of it and its functioning after creation. A technology is created with intentional design, but this kind of design is very different from art design. Technological design aims at certain function with direct or potential utility. In contrast, art design follows the principle of beauty. But in my opinion it's not right to interpret beauty as formal. A technology functions when it's used.

- Technology as Volition Volition is associated with will and decision. Certainly we have to make decisions in realizing the functions of a technology. But volition is focused on something beyond technical considerations. Volition is more concerned with using a certain technology, with its functions, to achieve some further goals, such as economic growth, military might, etc. Therefore, when looking at this aspect we put technology in a larger socio-cultural context, rather than examine it by itself.

- The three typical Western attitudes toward technology

- Ancient skepticism

- Enlightenment optimism

- Romantic uneasiness

The engineering view of technology was held by engineers, or at least people with solid engineering background. However, the view was well beyond professional common sense or preliminary intuition, but with philosophical depth. Generally engineers have good opinion about technology. The reasons why Germany dominated this view can be identified as follows: the rise of Germany in science and technology and more importantly German philosophical tradition.

The humanities view of technology was held by people with strong humanities, but minimal engineering background. They tended to take a general view of technology from outside. Their focus was on the relationship between technology and culture and most often their opinions of technology were critical. Of the four people discussed here Mumford and Ortega's views of technology were moderately critical, whereas Heidegger and Ellul's were extremely critical.

The framework Mitcham proposes highlights four facets of technology. They are object, knowledge, activity and volition.

In the Epilogue Mitcham elegantly applies his framework to the three typical Western attitudes toward technology. I add the word "Western" on purpose. To me these three attitudes bear the mark of Western culture and I'll compare them with the basic Chinese attitude below. Here I briefly put the three attitudes in the framework of Western culture. Compared with Chinese culture the Western culture is a religious one. In both the ancient Greek myths and Christianity we can discern the distinct dichotomy between human and God(s). This is the most fundamental character of Western culture. It's the basic framework within which all Western thoughts traditionally played.

Attitude toward technology: Technology is bad but necessary, or technology is necessary but dangerous.

Cultural interpretation: In ancient Greek Gods dominated humans. The world of Gods was primary and the world of humans secondary. Technology as the creation of humans was certainly inferior to the creation of Gods. The main objective of life was to move closer to Gods. Technology was naturally deemed as imperfect, or even corrupting to a certain degree. The case was not changed with Christianity.

Attitude toward technology: Technology is both good and primary.

Cultural interpretation: Enlightenment to a large extent lifted the status of humans. However it did the lifting through emphasizing reason, which was universal, restrictive, simplistic and foundationalistic. On the basis of this insufficient liberation of humans the traditional dichotomy between human and God was transformed into the dichotomy between humanism and scientism. The dominance of technology was a very natural phenomenon in the scientific worldview.

Attitude toward technology: Modern technology is not bad but secondary, or modern technology is monstrous, both powerful and ugly.

Cultural interpretation: The humanism-oriented romanticism worked as a counterweight of Enlightenment in the modern age. Its ambivalent attitude toward modern technology resulted from the incompleteness of Enlightenment. On the one hand it acknowledged the progress that had been brought about by modern technology. But on the other hand it put the emphasis on imagination and creativity, rather than reason.

B. Classical philosophy of technology

When people say "classical philosophy of technology" today they roughly refer to the humanities view above called by Mitcham. According to Brey, it has the following common characteristics:

- Generalization Classical philosophy of technology took a general view of technology from outside. It treated technology as a black box, a whole entity. It put its sight on the relationship between technology as a whole and other fields of society and culture.

- Determinism Classical philosophy of technology emphasized the deterministic power of (modern) technology. It tended to ignore the context of the creation and functioning of technology.

- Pessimism Classical philosophy of technology normally took a critical stance on (modern) technology. This negative attitude often resulted in pessimism.

This summary doesn't apply to all the classical philosophers of technology with the humanities view. It fits well with Heidegger and Ellul, but not Mumford. In my opinion, Mumford's view of technology was general, but neither deterministic nor pessimistic.

C. The empirical turn

The so-called "empirical turn" is said against classical philosophy of technology. Empirical is the opposite of generalized, but all the above characters of classical philosophy of technology were changed. Correspondingly philosophy of technology after the empirical turn has the following distinct features:

- Opening the black box Trying to open the black box of technology is the basic common feature of the empirical turn. When the box is opened two things in it become salient. One is specific aspects of technology. Technological object, knowledge and activity as discussed by Mitcham are all important aspects. The other thing is specific technologies. It's been discovered that not all technologies are equal. Different technologies may have quite different characteristics.

- Co-influence and co-evolution of technology and culture As a result of attention to details, technological determinism becomes untenable. Championed by social constructivism the whole process of technological creation and function are put in the large socio-cultural context. The prominent theories of the culture-ladenness of technology include Winner's politics of artifacts, Feenberg's underdetermination and Ihde's ambiguity theses. Therefore the relationship between technology and culture is revealed to be bidirectional.

- Steping out of the gloomy view With technological determinism debunked technology is no longer viewed as autonomous and beyond any human control. If modern technology has brought about many issues, these could be addressed, at least to a certain degree, not just through developing more advanced technologies as naive optimism suggests, but deliberate steering of technological development. Technological assessment and corresponding policy have spread to many countries.

D. Bridging the two views

The dichotomy between empirical and classical philosophies of technology and that between engineering and humanities views of technology don't exactly correspond to each other, but they are closely related. One thing needs to be pointed out: the traditional engineering view of technology was also very general compared with contemporary theories. So the empirical turn is more evolution of the field than conceptual shift. On the other hand the empirical and engineering views are well aligned with each other. Since the empirical turn one could discern that attention to details has put many general issues of modern technology aside, which was the major concern of classical philosophy of technology. Therefore the dichotomy ends up with one between the micro and macro views.

However, without the concern with general issues philosophy of technology could be degraded to ethics of specific technologies. Both empirical details and general issues are important. What's urgently needed is to combine them into an organic system. Mitcham's book is apparently an effort toward bridging the two views. If we could still regard technology as a box, there is no reason why we cannot both have an inside view of the box, and at the same time don't forget that the box is located in a large context. In fact the inside and outside views, or the micro and macro views could benefit each other if we don't hold the presupposition that they are inherently incompatible.

II. Existing Theories

A. The mono characterization: technology as applied science

A once dominant view of technology was that technology was applied science. The general assumption was that science discovered general laws of nature, whereas technology applied scientific discovery to solving specific problems in human life. The application of science in technology could happen in two basic ways: knowledge application and method application. Bunge clearly distinguished two types of technological theories: substantive and operative technological theories. The former was a direct application of scientific knowledge, whereas the latter resulted from applying scientific method. A general implication of this mono characterization of technology was that, the whole phenomenon of technology could be explained by science.

This turns out to be a very simplistic view of technology. The phenomenon of technology is in fact much more complicated than applied science. As we'll see below, it captures one important element of technology, but leaves out other essential aspects.

B. The dual characterization: the physical and functional aspects of technology

The mono characterization of technology is based on the scientific worldview. Although it recognizes the connection between technology and human need, the latter doesn't cause any issue, because human life is simply included in the scientific territory. The dual characterization just focuses on this issue. Its basic assumption is that some aspect of human life (intentionality) is beyond physical explanation.

- Multiple realization and reductionism Multiple realization is the phenomenon where the same function could be achieved through different physical means (structure and mechanism). It makes explanation of function through physical realization invalid. Therefore function has to be explained in terms of relation. For instance, a clock cannot be defined in terms of its internal structure and mechanism, but its general function, the ability to tell time. Now the issue becomes how to define the ability to tell time in physical terms. An effective reduction has to satisfy the following requirement: a functional kind must be mapped into a physical kind (like temperature and kinetic energy of molecules). We might be lucky in the case of a clock. Try to define the function of a book in physical terms.

- Proper function, accidental function and malfuntion Provided we could define all the functions of technical artifacts in physical terms, we have further issues. For instance, irregardless of how a copier is constructed (laser or inkjet) we define a copier as a machine that can duplicate certain images from one hard media (paper, plastic, etc.) onto another. Suppose one day the copier breaks down and stops functioning. Now the question is, is it still a copier or not? According to the above definition it is not, but this is against our normal practice. We call it a malfunctioning copier. The reason why we still call it a copier is that it is designed as an artifact with that particular function in mind. We may call this the proper function of an artifact. Malfunction is said against proper function. The mono characterization cannot handle the phenomenon of malfunction. Related to this, it cannot differentiate proper function from accidental function either. Using Kroes's example, a Newcomen steam engine is called a steam engine, but not a heater, although it also generates heat when it runs. What matters in both cases is the design of an artifact, an intentional act of human beings.

Compared with the naive mono characterization the dual characterization is a big improvement. It can handle more technological phenomena. But in my opinion it still falls short of addressing all the subtleties of technology. It reveals the close connection between technology and human intentionality besides science. However, it confuses the subtle difference between intentionality and intendedness. Technological function is motivated by and based on human need and hence closely related to human intentionality. On the other hand, technological design is an intended action. The two don't necessarily match. Generally we need further differentiation.

- Proper use, accidental use and redesign The life of a technical artifact doesn't necessarily stop at its original design. When its use matches the original design we say it's used properly. Besides proper use there could also be accidental use. When a stack of books are used as a stool, they are used in an accidental way. Further an existing artifact may even be redesigned to serve a new function. Transistors were invented to amplify signal in an analog circuit, but later they were also used in a digital circuit to realize certain logic. Accidental use can be regarded as degenerated redesign. In redesign an existing artifact obtains new proper function. Accidental use and redesign complicate the phenomenon of technology, but they could be handled with the dual characterization.

- Intended function, unintended function and side effect The function in the dual characterization is predominantly intended function. It's intended in the design process. However, once a technology is put to use, it's actual function could be more complicated than that. In an accidental use the function involved is still intended. But besides the intended function there could be many functions which are unintended. One important type of unintended function is side effect. Side effect is not only unintended but also unwanted. Since side effect is still (negatively) related to human need, it's connected to intentionality, although it's unintended.

- Technological lifeworld or second nature Side effect already causes some trouble for the dual characterization. But what are more troublesome are those functions which have nothing to do with human intentionality. Once a technology is put to use, it obtains certain autonomy and has its own life. It could come back to shape human behaviors. In that sense it becomes second nature along with nature, an integral part of our lifeworld.

III. The Triple Characterization

Compared with Mitcham's framework of the four facets of technology, the triple characterization of technology is intended to put more emphasis on the unique characters of technology. Object, knowledge, activity and volition are aspects shared by many human activities. They are more useful for sorting out various studies of technology than demarcating between technology and various other cultural areas. What's more important, the triple characterization demonstrates the connection between technology and other social/cultural areas at the same time of demarcation. And since it's also details oriented, it provides a solid foundation for bridging the micro and macro views of technology.

A. The three elements of technology

In discussing the dual characterization of technology we've reached the viewpoint that we need to further distinguish design from function besides the physical aspect of technology. To be precise, physics is only one part of the foundation of technology. There are also chemical and biological technologies. So the physical aspect should better be replaced with scientific aspect. Therefore, we have science, design and function as the three elements of technology. These three elements capture the three basic characteristics of technology: It's nature-restricted, human-made and human-used.

- Science Here science is mainly understood in the metaphysical sense, the sense of laws of nature. Of course, all human activities without exception are governed by laws of nature. But the reason why we can treat science as an important aspect of technology is that laws of nature are crucial to technology. It's not the case for other activities, such as art. The scientific element of technology in a part is also understood in the epistemological sense. In this sense technology is created on the basis of certain scientific knowledge.

- Design On the other hand, technology is always created with certain intentional design. The means and end can be clearly identified in technological design. Certain function, or set of functions with human utility always stand in the center of the end. But the major part of design is about the specific means to achieve the end. And scientific knowledge plays an essential role in figuring out the means. However, technical consideration is not the only design factor.

- Function Technology is created to serve certain functions. These are intended functions. They are also called proper functions. When a technology is put to use its actual functions could be different from what are intended. Malfunction happens when the intended function is not realized. Side effect is unwanted function. Certain functions could even go beyond human intentionality. In that sense technology becomes a part of nature.

We can see the above three elements of technology are not separate components, but intertwined aspects of the same entity. There are both scientific and functional elements in design. Science definitely stands under function. And design to a large extent determines function.

B. Technology and science

People's understanding of the relationship between technology and science has gone through dramatic development. We can identify three different phases:

- Traditional science and technology Traditional science was under-developed and shallow compared with modern science. Human curiosity in nature was closely associated with utility because life was harsh. People's limited leisure time was mostly devoted to other areas than science. In this phase the boundary between science and technology was very vague.

- The rise of modern science With the emergence and rapid development of modern science science became a distinct and prominent area of human activity. A major result was the separation of curiosity from utility. Science was described as sacred, pure and detached human endeavor. It's clearly distinguished from technology, which served human needs and hence was deemed as somewhat contaminated. In this phase science gained superiority. This was reflected in the popular view that technology was applied science.

- The emergence of big science The development of modern science finally reached the stage where its further advancement was heavily dependent upon technical equipments and instruments. These equipments and instruments had to be created with modern technology. Now the dependency relationship between science and technology seemed to be reversed. Authors were eager to point out that technologies invented in the first stage of the Industrial Revolution were created independent of modern science. Radical authors even claimed that science was in fact applied technology.

On this background my view on the relationship between technology and science can be summarized as follows:

- Technology and science are two quite different human activities, although they are intertwined.

- Motivation: utility vs. curiosity The direct goal of technology is certain useful functions, whereas that of science is making sense of what's happening in the world.

- Knowledge: know how vs. know why Technology cares about how to achieve certain functions, whereas science is concerned about why something is happening that way.

- Activity: creation vs. interpretation Technology is an activity of creation, whereas science interprets the existing world.

- Object: artefacts/procedures vs. theories Artefacts and procedures directly interacts with the world, whereas theories are passive, at least they don't have direct influence on the world.

- We need to take a broad view of science, with modern science as a special case.

- Mathematical accuracy All the processes in the world can be modelled in accurate mathematical terms.

- Universality The processes are governed by universal laws.

- Mechanism The parts of a whole can be handled independently of its context.

- Reductionism Superficial phenomena can be reduced to the corresponding fundamental phenomena with a "nothing but." For instance, temperature is nothing but the kinetic energy of molecules.

- The scientific element of technology has been persistent in all the developmental phases.

Technology and science were generally intertwined, especially in the first and third phases above. However we still can distinguish them in the following important aspects, corresponding roughly to Mitcham's four facets:

The dramatic success and dominance of modern science had foster a biased view of science. In the first half of the 20th century this view was represented in logical positivism, according to which science had superiority because it was based on solid empirical verifiability, whereas all the other areas of learning were disdained as "metaphysics." This view was debunked step by step, through historicism, social constructivism and post-modern criticism, in the second half of the century. Now a widely accepted view is that modern science has a set of peculiar assumptions. We may list the following:

What's at issue is not the specific content of each of the above assumptions. The success of modern science was built on these. The problem rises when these assumptions are extrapolated to the whole world. On the other hand, demonstrating the invalidity of the extrapolation makes pre-modern and post-modern science meaningful. In a sense post-modern science can be built as a synthesis of pre-modern and modern science.

Dismissing the peculiar assumptions of modern science is not meant to blur the boundary of science. The scientific narrative is not one on a par with a novel, as some post-modern critics claimed. If scientific theories may still be regarded as human creation, then this type of creation has much less freedom than that in a piece of art work. Anyways, its goal is to make sense of the existing world. It has to first respect the world and then make sense of it. Adherence to empirically verifiable reality and systematic theory building with mathematics should be the two basic essential features of scientific activity, although they don't have to be as accurate and universal as Newtonian Mechanics.

The scientific element of technology is easier to discern with the broad view of science. Contrary to the claim that technology had developed without any guidance of science up to at least the Industrial Revolution (Watt didn't use modern science in inventing the steam engine), a particular technology has always based on some understanding of the world. If we don't equate science and modern scientific theories and understand science in the broad sense, the scientific foundation of technology has been there all the time. Traditional science might not be as accurate and universal as modern science, but both mathematics and experimentation had been used before modernity.

C. Technology and art

D. Technology and economy

E. Technology and ethics/politics

F. The triple characterization of technology as a way of bridging the two views

IV. The Cultural Quadrants

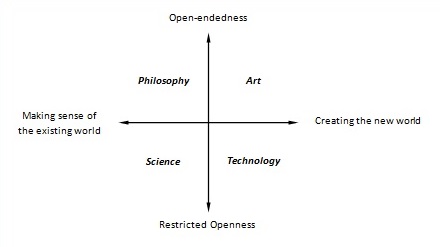

Based on the above characterization of technology I'd further propose the cultural quadrants as depicted in the following diagram.

Human spiritual activity in the form of culture may be divided into four quadrants along two axes: creativity and openness. The two poles of the creativity axis are making sense of the existing world and creating the new world. Creating the new world is definitely a standard form of creativity. But making sense of the existing world is also a form of creativity. When we make something, that something is something new. So we are creating something. Just in this case the thing created is the sense, in the form of theory, of the world, but not the world itself in the strict sense. Once something new is created by human beings, it becomes part of the existing world. This includes both the created world in the strict sense and the created theories. The two poles of the openness axis are restricted openness and open-endedness. Again both are open in a sense, but one type of openness has some kind of restriction whereas the other doesn't. Generally all human spiritual activities are open creation, but we could still divide the area into different fields with subtle differences along the two basic axes.

The advantage of this division is that it offers clear demarcation of the major cultural fields. Specifically it neatly puts science, technology, philosophy and art into one of the four quadrants respectively. Next we look at each field/quadrant in detail:

- Science in the lower-left quadrant The aim of activities in this quadrant is to make sense of the existing world. They are open activities, but have fundamental restriction. To say that the aim of science is to make sense of the existing world seems to be a common sense. It's commonly accepted that the basic goal of science is to construct a theory of the world. However, the interpretation of this goal has undergone significant evolution, or rather revolution in the 20th century. At the beginning scientific theory was regarded as representation of the world like a "mirror of nature" (logical positivism). But then historicism (Kuhn) and further post-modernism (Rorty, Latour, etc.) totally debunked that naive view, so that scientific theory became a type of human creation in a particular historical (I'd add, cultural) context. In this way science is not an activity of timeless angels, but of human beings with flesh and blood. Then where lies the restriction? If the aim of science is to make sense of the exiting world, then the existing world naturally becomes a restriction. But further restriction of science lies in its methods, specifically mathematics and empirical proof. At first glance, these two look so incompatible. One is based on extreme abstraction while the other on utmost concreteness. Yet modern science elegantly and effectively combines the two poles together. However, with the elegance and effectiveness it also builds the restriction in itself. In a sentence, it leaves out all the things in between.

- Philosophy in the upper-left quadrant Traditionally most part of the left side of the diagram above was the territory of philosophy. Newton's master piece was titled Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Once the young man grew strong and gained significant independence he quickly showed arrogance and became defiant to his dad. But unfortunately each time he got into deep trouble he still had to come back to dad. And that's where the analogy stops. In the human world, a young man will finally grow mature and the dad will grow old and die. That won't be the case with science and philosophy. Modern science was born from philosophy with some essential birth traits. They directly contributed to its dramatic success, but on the other hand put a boundary around its Spielraum. All the area left out by science still need to be taken care of by philosophy. Philosophy is open-ended because it doesn't have predefined premises or methods. It doesn't assume that everything can be described with mathematics, or every theory has to be proved with empirical evidence. In fact, anything can become the object of philosophical inquiry, including philosophy itself. It's often derided that we can never have philosophers agree on anything. With its open-endedness, that's exactly what philosophy should be.

- Technology in the lower-right quadrant We're now crossing a more important divide. Activities on the left or right side are more intimately related than those on the top or bottom. As we've mentioned modern science grew out of philosophy. Traditionally art and technology were also mixed together. Activities on the left cannot do without logic. But logic plays a secondary or minimal role on the right. Modern neural science has revealed the correspondence in the human brain. In fact, the left brain is more in charge of the left side while the right brain more in charge of the right.

The traditional intimate relationship between art and technology was reflected in words. In Greek the word Techné referred to both art and technology in the modern sense. And in Chinese ji 技 and yi 艺 were often talked about together. Like art, technology has been an indispensable part of human civilization since the making of fire and stone tools. They both create something which doesn't belong to the existing world. However, technology has a restriction which art doesn't have. A technology must have certain utility, or at least potential utility. The aim of technology lies beyond itself. Once we reach technology for the sake of technology, then we know it's out of control. Due to this restriction, the end and means of technology are closely bundled. So it's not essentially free from the existing world.

- Art in the upper-right quadrant At last we arrive at the freest human spiritual activity. On the one hand, art aims at creating something new, so it doesn't have the restriction of the existing world. Its method to a large extent depends upon the existing world, but not its content. The method and content of art are uncoupled partly due to the following fact. On the other hand, the creation of art is not restricted by an outside goal. Utility is not a consideration of art per se, although it's the case in applied art. There is no other outside goal either. So the content of art is determined by itself and art is self-contained human creative activity. This self-containedness doesn't result in closure, but on the contrary more openness. Therefore, art has more diversity even than philosophy. After all, art is the highest expression of human life.

Two important comments need to be made here regarding the cultural quadrants. First, science, technology, philosophy and art are four typical or representative fields in the four quadrants. Other cultural fields can also be put into the quadrants. Some may end up in the boundary area. For instance, religion is another key cultural field. Traditionally people talked of science, philosophy, art and religion as the four fundamental cultural fields. Now we've separated technology from science and granted it foundational status. Then where should we locate religion in this new picture? Religion primarily provides a theory of the world, so it should belong to the left side of the diagram. Next, is the theory open-ended? Apparently not. Since it has predefined premises, it's restricted. In the Introduction to A History of Western Philosophy Russell put philosophy in between science and religion. Now we have quite different relationship among them. Second, activities in the four quadrants penetrate into one another. The mutual penetration of science and technology is obvious. Science and technology are more intensively used in art creation. Philosophy and art are inseparable in some works. There are philosophies of everything, although the science of philosophy, the technology of philosophy, or even the art of philosophy all don't make sense.