Research Areas and Projects

Research at Home: Philosophy of Technology

Developmental Introduction

Philosophical Characterization of Technology

Chinese Philosophy of Technology

Developmental Introduction

To put my current research in good context, it's not enough just to outline my general framework of thought, but also to show how it has come about. My philosophical thought has undergone dramatic development. In some respects it even involved 180 degree turns. This has allowed me to reach several fundamental poles in philosophy: scientism and humanism, Anglo-American and continental European philosophies, Western and Chinese philosophies, Confucianism and Taoism, etc. Finally I'm striving for a grand synthesis.

A special political context made us exposed to philosophy as early as high school. The Marxist political economics and philosophy was an essential part of the National College Entrance Examination in China. We were taught that philosophy was theory of world outlook and it's about general universal laws of the world whereas specific sciences took care of special areas. (Now I still find Marx's general criticism of capitalism in Das Kapital valid, but I've discarded almost all the philosophy part.) Somewhat related was the naive scientistic worldview formed in the process of studying natural sciences, especially physics. According to this view all the processes in the world were governed by scientific laws and it's hopeful that all the laws could be reduced to a few, and ideally one, most fundamental ones. So I was fascinated by Einstein's Grand Unification Theory.

At University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) I was eager to study philosophy of science, including Russell, the Vienna Circle, Popper and Kuhn. Logical empiricism overemphasized the empirical aspect of science. Logical empiricists believed that given raw empirical data they could build the world with logic. In Der logische Aufbau der Welt Carnap tried to do exactly that, but he apparently couldn't get off the ground. As an improvement Popper highlighted the theory building aspect of science. For him conjecture and refutation were as important as verification. At that time I didn't appreciate Kuhn much, but felt something was wrong with empiricism, especially with Hume's criticism of induction. Causal laws didn't seem to be derived from empirical facts. Russell's A History of Western Philosophy introduced a whole set of Western philosophers to me. Later I realized that, from his empiricist perspective he got the majority of modern philosophers wrong, just as someone pointed out. But it's undoubtedly an excellent one-volume introduction.

I spent more time to read works in various social sciences, including psychology, pedagogy, economics, sociology, anthropology and history. This was in parallel with intensive study of advanced mathematics and physics at USTC. The more I studied social sciences the farther I found the scientistic view from reality. With so many different kinds of phenomena it seemed very unlikely that we could find just a few scientific laws to explain all of them. Besides, I ran into problems which probably lay beyond the realm of scientific inquiry. The mathematical-empirical method seemed to be irrelevant to moral and aesthetic issues. At this time I still held the notion of world system. To me the whole world was still arranged according to some universal principles. If science fell short of grasping them, philosophy could be up to that task. What I was taught in high school still had its shadow on me. In fact, I did find in Hegel's gigantic system an exemplary model.

The 1980's in China was vibrant not just in introducing Western thoughts with unprecedented intensity and scope after decades of hunger, but also in pondering and discussing the direction of Chinese modernization in an active and vehement way. In the field of philosophy Li Zehou stood out. Based on in-depth study of Chinese history of thought he shed some shining light on Chinese modernization. I found many of his insights and proposals attractive. And the problem of Chinese modernity has been an essential part of my thinking ever since. In my "Bachelor Autobiography" 《学士自传》 I summarized the development of my thought up to that point.

At Peking University (PKU) I received formal philosophy training. We studied a bunch of works by major Western philosophers. Of all the philosophers we studied Descartes, Kant and Heidegger were the most important for me. With the proposition Cogito ergo sum Descartes ushered the new theme of modern Western philosophy. After that cogito, the thinking subject, became a central topic of Western philosophy. This was often called the epistemological turn. Around the question of the origin of human knowledge two camps were formed, the continental rationalists and the British empiricists. The first camp was championed by Descartes (France), Leibniz (Germany) and Spinoza (Netherlands), whereas the second by Locke, Berkeley and Hume (all from England). Generally speaking the former camp held that human knowledge originated from inside the thinking subject whereas the latter argued that it came from outside. When we think about it a little deeper neither seems to provide a satisfactory theory. If we isolate the subject from the outside world then how is knowledge about the world possible? On the other hand, Hume finally showed that starting from the raw images of the world at least some part of human knowledge couldn't be obtained.

On the background of this dilemma Kant proposed a brilliant solution which he called his Copernican revolution. At first glance his solution was just straightforward combination of the theories of the opposing camps. If either can't provide a good solution, why don't we combine them? In Aristotelian terms, the outside world provides the matter and the thinking subject offers the form, and then we have knowledge as result of applying the form to the matter. If that's all the solution was about, then in what sense was it a Copernican revolution? There must have been something more. For centuries people had thought that the Earth was the center of the universe and the Sun went around us day after day. Copernicus first proposed the idea that the Sun was in the center while the Earth went around it. Similarly, Kant's theory revealed that the world as we humans saw it was merely the phenomenal world with human idiosyncrasies. It's made possible by space and time as the transcendental forms and fundamental logical categories and principles, such as causality. When anything happens we think there must be some cause for it. This basic notion of causality was not obtained from induction on the basis of repeated experience - Hume pointed out this path was not viable. Rather, it's a built-in part of the human mind. In other words we cannot see the world as a non-causal one. But this is at best our world. The noumenal, or "absolute", world, Ding an sich is unknowable to humans. Kant marked it as a big "X." And this was where the analogy to the Copernican Revolution ended.

Kant called his theory "transcendental idealism." This set the backdrop for further development in Western philosophy. In fact, idealism and transcendence in Kantian philosophy stimulated two basic directions of development respectively. The first was German classical philosophy. Kantian idealism going through Fichte and Schelling was transformed into Hegel's enormous system of the self-realization of the Weltgeist. Once the absolute spirit had completely realized itself, it became static and dead. So did Hegel's system. The second direction didn't go against subjectivism, but transcendence instead. For Kant space and time, the fundamental categories and principles were all given. Phenomenology was initiated by Brentano's study of intentionality, but ended up an in-depth analysis of the thinking subject. Starting with the subject and adopting Descartes's method (in the new form of epoché) phenomenology plunged into the same predicament: struggling to get out of the abstract subject in order to reach the object.

From this predicament Heidegger suggested a way out, another brilliant and revolutionary solution. According to him Husserl, his teacher, picked the wrong starting point. To figure out the relationship between human and the world we shouldn't start with an abstract subject staring at an object, such as a hammer. Rather, we should begin with how the subject and the object interact with each other in our everyday life, such as when we use a hammer skillfully without being conscious of its existence. For Heidegger the second mode, Zuhandenheit, has ontological priority over the first mode, Vorhandenheit. In Zuhandenheit we could reveal that the human existence, Dasein, intrinsically carries a world with it. Dasein is congenitally In-der-Welt-sein. The meaning of being has to be sought from this special existence, not the other way around. Further Heidegger highlighted some deeper structures of human existence, including Sorge as the fundamental mode. And from there he went on to explore the existential basis of time. Compared with Kant, space and time were no longer presupposed transcendental forms, but found their bases.

Having learned German for a couple of years I was able to read Kritik der reinen Vernunft and Sein und Zeit in their original language. Both works were difficult, although in different ways. But reading them in German was definitely rewarding. With the influence of these two works I completed the transition from scientism to humanism. They both clearly demonstrated me the central status of humans, in ontological sense. I finally got out of the shadow of universal laws. Now for me the human existence was essentially free and open and therefore beyond the scope of universal laws. This new belief in humanism/liberalism permeated the papers I wrote in the next phase.

The first paper was my Master thesis, titled "The Reference of a Proper Name: On Kripke's Naming Theory." Kripke proposed a causal naming theory of a proper name. According to this theory, once a proper name was given to an individual in a so-called "naming ceremony," its reference would be fixed no matter what happened later on. And it could go down history through some kind of causal chain. So the mechanism of the reference of a proper name (e.g. Aristotle) was quite different than that of a descriptor (e.g. the teacher of Alexander the Great). In a different possible world the latter could be different whereas the former kept fixed in all possible worlds. In my paper I challenged the meaning of this absolute causal chain. I argued that the referring power of a proper name could only expand to non-witnesses of the naming ceremony through the spread of human knowledge. Therefore it could not happen in the metaphysical world, but only in the epistemic world.

At University of Connecticut (UConn) I was exposed to the whole spectrum of analytic philosophy, from philosophy of language through philosophy of mind to political philosophy. I was quite amazed to find out that the analytic method could be used well on political issues. Given the humanistic belief formed at PKU the stance I took in my papers was quite off the main stream in analytic philosophy. In studying philosophy of language and philosophy of science I could fully appreciate Quine and Kuhn. Regarding the status of scientific knowledge Kuhn was more radical than Quine. Whereas Quine maintained that scientific knowledge was holistic Kuhn argued that it's historic. In the seminar paper for theory of knowledge, "Goldman's Theory of Justification," I criticized the standard definition of knowledge as justified true belief. I argued that truth couldn't be used as a separate criterion of knowledge, because truth in the sense of correspondence between belief and reality was not verifiable for humans as a community. One person's belief could be verified by another person, but what could guarantee the truth of the second one. We could go on and on, but just couldn't find a solid ground in the human world to lay the truth on. Therefore knowledge could only be justified belief. The justification pointed to the sociology of knowledge. Together with Quine's holism and Kuhn's historicism this provided another way to challenge scientific realism.

My papers in philosophy of mind and political philosophy were directed against reductionism. In high school I took physicalism and materialism for granted. At this moment I tried hard to debunk them. The landscape of philosophy of mind was kaleidoscopic. There were a bunch of views concerning the nature of mind, but three major levels were involved: physico-chemical processes in the nervous system, functional behaviors of the brain and consciousness. With multiple realizability the reduction of function to physico-chemical process was quite difficult to defend. So major debates occurred around whether we could reduce consciousness to function. With the humanistic belief my stance on this debate was obvious. It boiled down to defending human dignity. The reduction involved in political philosophy was of a quite different kind. Since Hobbes mainstream modern Western political theories have been starting with the individual, the rational individual to be precise. So a major task of political philosophy was to construct a polity out of individuals. The contractual theory has been the dominant one since the beginning and has been kept up to Rawls's A Theory of Justice. The argument in my paper "Communal Justification, Role Identity and Political Obligation" was against this individualistic contractual theory. The main idea was that political obligation (such as obeying certain laws of a country) was not based on individual voluntary choice. A person couldn't choose his/her home country, just like he/she couldn't choose his/her parents. Even an immigrant could only choose a new country as a whole. So political obligation had to be based on some communal justification. The thought behind this argument was the irreducibility of a community. Now a problem came up. There seemed to be a conflict between an irreducible community and personal freedom. This was resolved in my seminar paper for philosophy of social sciences, "Social Laws and Individual Autonomy." In fact, the seeming conflict between social laws and individual autonomy was just based on the reducibility of social phenomena to individual ones. If they were processes on different levels there wouldn't be conflict between regularity on one level and freedom on the other.

After a year of staying in the US I wrote "Records of Thought" 《思想录》. In it I summarized my transition from scientism to humanism/liberalism. I also recorded my first impression of the American society. Generally I felt a sense of liberation, but I also alluded to the gloomy side of the society. As I obtained more experience and deeper understanding that negative feeling grew stronger. Life in a foreign culture put me at the edges between it and my native culture. It gave me a special perspective and allowed me to reflect on both with more ease. Since the Chinese and American cultures were so different, little could be taken for granted. In phenomenological terms many of the hidden assumptions of the two cultures became thematic. And I was in a position with a side-by-side view. This greatly changed my understanding of both sides. On the American side, first-hand experience helped to correct presumption. The Marxist-Leninist gloomy view of a capitalist society had been replaced with a rosy imagination of a free and prosperous American society long before I stepped on the American soil. At last I reached a more balanced conception. On the Chinese side, conflicts between the two cultures dramatically revealed my cultural identity. It helped me to move out of another shadow cast by the education I received in China: the cultural self-denial as a result of the impact of Western modernity.

At University of Massachusetts (UMass) the focus of my study in computer science was artificial intelligence (AI). At first I was captivated by the flamboyant optimism in the field. But after I got closer to reality I was converted to Dreyfus's preaching. His criticism of AI was based on Heidegger's Sein und Zeit. The basic idea was that human intelligence couldn't be based only on "brain in a vat" but the whole human body. Compared with a brain in a vat the whole body on the one hand was situated, on the other hand was driven by desires and had emotions. Later I realized that, by emphasizing the importance of human body for cognition Dreyfus pushed Heidegger's philosophy another step forward, with Merleau-Ponty as a middle link. The human body provided a further foundation for the human existence as analysed in Heidegger's philosophy. If we keep going and trace the foundation of human body we could naturalize epistemology in a genuine way. This is to be distinguished from naturalized epistemology based on the scientific study of human cognition, which essentially presupposes brain in a vat.

In the meantime the study of Chinese philosophy became urgent again. Now Feng Youlan (Fung Yu-Lan) was the principal guide. His education background and general stance made him a good match. Unlike Li Zehou he received Western education and was familiar with Western philosophy. Contrary to Hu Shi he took a defending stance on Chinese philosophy. In his famous book A Short History of Chinese Philosophy he unveiled the essence of Chinese philosophy to the Western intellects in lucid terms, often drawing comparisons between Chinese and Western philosophers and key ideas. The most impressive were the non-religiosity of Chinese philosophy, its special method and the theory of the four spheres of living. In addition to philosophy, from reading Chinese histories written by Western sinologists I also obtained a different view than I was taught.

Shortly after I started to work at Novell I wrote "Framework of Thought" 《而立构想》 to record recent development, especially my second transition of thought. After briefly recounting my thought path I got into the main parts of the essay: criticizing Western modernity in respects of its two pillars, scientism and democracy, and constructing Chinese modernity. My view of scientism had been developed for a long time. In the essay I specifically targeted the notion of "a theory of everything" recently popularized by Hawking's A Brief History of Time, Watson's Behaviorism, la Mettríe's Man a Machine and finally "strong AI." The common feature of all the targets was reductionism. The reflection on democracy only happened after I went to the US. The basic notion I identified behind democracy was what I called "voluntary liberalism." It's embodied in the principle formulated by Mill: An individual shouldn't be interfered to do things at his/her will unless his/her deed causes harm to others. His/her own good is not a sufficient warrant of the interference. The basic symptom of this principle as I detected was bipolarization of the society - coexistence of the high culture, with flourishing arts and sciences, and the culture of decadence, with violent crimes, drug addiction and prevalent pornography. With respect to constructing Chinese modernity my ideas recorded in the essay were preliminary. These would undergo the most development in my dissertation later. The general principle was quite clear. Chinese culture had to be the core of Chinese modernity. It's modernization of Chinese culture, not Westernization. I also highlighted some key ideas, including naturalism, the ideal of the sage and elitism.

"Framework of Thought" was a milestone in my thought development. It summarized the two major transitions of my thought and set the framework for further development until I made a major upgrade in my dissertation around a dozen years later. During the several years I stayed in Utah one of my main tasks was to systematically study Western classics, including close to 200 works by about 50 authors. Shortly after the 911 attack I had the hunch that this could mark the turning point of American history. I became more and more convinced by what happened afterwards. On the other hand, the promising development on the other side the Pacific Ocean resonated with my new-found cultural identity. Finally I made the decision to move back to China. But I stayed for over two years more to complete existing plans and make necessary preparation for the move. During my last days in the US I composed "Return Trilogy" 《回归三部曲》. It handled return in multiple layers and generally lay in the previous framework. That concluded my American Journey.

While I was experiencing the dramatically changed Chinese society after consecutive 8 years abroad, my initial excitement quickly faded away. After I reached a realistic assessment of the status of China, the old project of Chinese modernity became more urgent than ever. Two major tasks popped up to the top of my to-do list. First, I needed to prepare for the German expedition conceived long time before. As an integral part of the Chinese modernity project the main goal of the Germany expedition was to experience the European society. After years of work in the IT industry, reading and thinking I also wanted to get focused and crystallize what had been fermented in my brain. The form of conducting a PhD study in Germany came out naturally. The next thing was to pin down the subject of the study. Chinese modernity was a grand subject and apparently not suitable for a PhD study. I needed to hang my thinking in a grand project on a concrete topic. Philosophy of technology suddenly showed up as the best choice. Besides my strong technological background, technology was intimately related to modernity, but it also involved many concrete issues worth exploring. Although I had studied philosophy for many years philosophy of technology was a new field for me. Before I could write the proposal I had to read quite a few books. The second major task was to find an alternative place for longer plan. I grabbed a world map and tried to locate a place with the right distance from China. At last my eyes froze on a dot on the Equator. Right before I launched the Germany expedition I made a scouting visit in Singapore with my wife. After that the choice was confirmed.

Requiring me to abandon a well-paid IT job with a family at a relatively late stage of life and adventure in an unfamiliar society the German expedition demanded extraordinary courage, but it's also tremendously rewarding. It was a meticulously planned project and achieved most of its heavily preset objectives, except some unpredictable deviations. After several months of life in Germany I clearly discerned some major differences of the German from the American society, including the government's relatively heavy control of the economy and social life, a comprehensive welfare system with subsidies for high culture (museums, theatres, etc.) and last but not least, a remarkable environment consciousness. The Americans had a congenital preference for small government, but it's not the case in Germany. For one thing, all the residents were required to register their addresses to the government. This was unimaginable in America. With this new experience I had to think about Western modernity further. Now it became inappropriate to put a equal sign between Western modernity and the American society. That would be biased. Due to different cultural and historical backgrounds different Western countries had adopted different forms of modernity. However, this variation didn't prevent us from talking about Western modernity generally. Different countries could still share some common features. Besides we needed to take into account the fact that reforms had been made to the canonical principles recently. So we'd better treat Western modernity as a theoretical concept. Nonetheless the American society still had some priority. Due to its special history the basic principles of Western modernity seemed to be all fully implemented in America.

With national variation and historical evolution we need to adopt a "genetic" method in categorizing Western modernity. Rather than studying existing Western modern societies statically, we need to study how Western modernity came into being out of the traditional Medieval societies. Unfortunately Western modernity didn't come into existence with a single wave of magic wand. The Scientific Revolution took place in the 17th century, but universal suffrage was not achieved until the second half of the 20th. If we focus on the major events in Western modernization we could recognize a general pattern: Human individuals were liberated from traditional restrictions step by step, going through the cultural (Renaissance, the Religious Reformation & the Scientific Revolution), economic (the Industrial Revolution & capitalism) and political (democracy & human rights) realms in turn. The word "genetic" also has another meaning. It's not just about how a new organism is born, but what it inherits from its progenitor. So the genetic method has another focus on the continuity of Western modernity from the traditional Christian culture. Putting Western culture side by side with Chinese culture I could more easily detect this continuity on a deeper layer. Western modernity was not a complete breakaway from the traditional Christian culture, as some people once claimed. Rather, it carried the Christian culture on in a fundamental way.

The German experience worked as a catalyst for the fermentation in my brain to produce this new understanding of Western modernity. With this understanding I set out to deconstruct Western modernity, an essential step toward constructing Chinese modernity. Generally speaking the deconstruction of Western modernity was to separate the Western from the modern elements in it. With this separation alternative modernity to Western modernity obtained much playing ground. In this way modernization was quite different from Westernization. Specifically, in my dissertation I identified industrialization and individualism as two essential features of modernity. Compared with traditional agriculture, industry was a new production method based on easily relocatable automatic machines. This provided the material foundation for a modern society. On top of this foundation modernization was a process of individual liberalization, in economic, political and spiritual terms. However, Western modernity realized individual liberalization in a peculiar way. I recognized its general principle as egalitarian universalism. In capitalism, democracy and the scientific worldview equal individuals acted according to universal principles. Thus money, abstract personal will and reason became the dominant universal tokens in the realms of economy, politics and culture respectively. Under this universal principle all the particularities were regarded as backward and gradually wiped out. I could only trace this general principle back to the Christian belief that humans were brothers and sisters under the providence of the almighty God.

On the Chinese side I was eager to study Chinese classics, starting with the pre-Qin schools. Chinese philosophy of technology was planned as a case study in my dissertation. This time Needham became an important mentor. Li, Feng and Needham all took a different perspective of Chinese thought. Li's was an aesthetic one. His strength was in its origin and anthropological basis. Feng's was a perspective from Western philosophy. He was good at explaining it in Western philosophical terms. Needham's was one from a scientist. His emphasis was on natural philosophy. In reading Needham's series Science and Civilisation in China I got quite a few big surprises, including the geared wheels in the Shang dynasty, the water clock in the Song dynasty and the amazing south-pointing chariot based on deferential gear during Three Kingdoms. In the introductory and concluding volumes Needham handled Chinese philosophy and general issues concerning Chinese science and technology. The most important for me were organicism in Chinese philosophy and the general problem of his study of Chinese science and technology, known as the "Needham Problem." The basic question of the problem was, given China's significantly better preparation in technology why did modern science emerge in the West instead of China?

Standing on the shoulders of these three prominent scholars of Chinese thought and combining with my new understanding of Western modernity I tried hard to reach a new comprehension of Chinese tradition. Comparing with the dominant role of Christian belief in Western culture, along with Li now I could well appreciate the importance of shamanism for Chinese culture. I could more clearly perceive that when I studied Lun Yu (Annalects) again and I obtained similar observation when I studied Zhuang Zi the first time. If Li could claim that Confucius was a shaman, we could do the same thing to Zhuang Zi. In fact Zhuang Zi contained a story about how a great shaman scared away a mediocre one. However, Chinese classical philosophy was not shamanism any more. Finally I reached the idea of sublimational metamorphosis. Generally from shamanism to classical philosophy Chinese culture underwent a sublimational metamorphosis, with the spirits despritualized and humans sublimed. Specifically a set of transformations took place: the spirits were transformed into the spontaneous nature (Tian, Dao); the shaman into the sage; the training of shaman into personal cultivation; the shamanic ecstasy into the supermoral aesthetic state; the communication between the shaman and the spirits into the unity of human and nature. Inspired by this idea I saw a similar metamorphosis on the Western side, one from the Christian worldview to that of modern science. In this case the almighty God was transformed into the theory of everything and the dichotomy between the human world and the world of God into that between the human world and the scientific world.

Once I traced the Chinese and Western cultures back to their different forms of religion the contrast between them was much easier to understand. In contrast to Christianity shamanism was a primitive form of religion, where humans and spirits were mostly equal. Humans could please the spirits with sacrifices, but they could punish them as well. The spirits could cast their power toward humans, but humans could also influence the spirits with magic. After the metamorphosis in China humans were sublimed while spirits downgraded. As a result human affairs dominated classical philosophy. When this dominance was solidified in the Han dynasty, higher level religion had no chance to develop originally in China. This shaped a unique Chinese culture predominantly focused on the human world. It's unique because all the other major cultures were dominated by one higher form of religion or other. There existed a spectrum between the shamanic spirits and the almighty God, with the latter as the highest form of religion. Once Chinese culture branched out from shamanism it became essentially irreligious. That's the basis of the stark contrast between Chinese and Western cultures. In the traditional Christian culture there existed the fundamental dichotomy between the human world and the world of God. This cultural dualism was embodied in a series of new dichotomies in Western modernity. To name just the major ones, they included the dichotomies between mind and matter, subject and object, secondary qualities and primary ones, emotion and reason. Parallel to the relationship in the traditional dichotomy, the second terms in the modern dichotomies were considered as absolute, fundamental and pure whereas the first terms relative, superficial and somewhat contaminated. In stark contrast there didn't exist another world beyond the human world in Chinese culture. This cultural monism excluded all the dichotomies that existed in Western culture. The organic ontology was modelled after the human body instead of a machine and the whole worldview was holistic. Mind and body, subject and object, emotion and reason were all interconnected and inseparable.

With this new picture I started to realize important problems in Li, Feng and Needham's theories. Li characterized Chinese culture as "practical rationality 实用理性". "Practical" was meant to be in contrast with abstract reasoning and "rationality" in contrast with religious irrationality. Both parts became problematic to me. Although Chinese philosophy was focused on human affairs that didn't mean it's only concerned with pragmatic issues in everyday life. As expressed in Feng's theory of the spheres of living the ultimate goal of Chinese philosophy was to transcend daily life and reach the supermoral sphere. The pursuit of sageness was very idealistic indeed. To call Chinese culture practical was probably based on the confusion between abstract thinking and formal logic. Formal logic was not very useful in Chinese philosophy, but that didn't mean that Chinese philosophy was not abstract. To call Chinese culture rational seemed to be based on another confusion between religion and irrationality. Religion could be very rational. In fact a substantial part of scholastic philosophy was devoted to the proof of the existence of God with formal logic. The contrast between Chinese and traditional Western philosophy was rather one between humanism and deism than one between rationality and irrationality. Emotion and reason were inseparable in Chinese philosophy. It's no less emotional than rational. (In fact this was one of Li's own key ideas.) Meanwhile some parts of Feng's characterization also began to appear inaccurate. He proposed that the method of Chinese philosophy was negative. Instead of addressing some issues positively it chose to keep silence. By contrast I would claim that the method of Chinese philosophy was poetic rather than negative. Lun Yu, Dao De Jing and Zhuang Zi mainly adopted the exemplary 案例, aphoristic 警句 and fabled 寓言 methods - three important poetic methods - respectively. So the several dozens of chapters about Ren 仁 in Lun Yu were not definitions of the key concept of Confucianism as pointed out by Feng with reference to Plato's Dialogues. Rather, they were concrete examples where the concept could be applied. The fact was that, such a complex concept as Ren couldn't be defined at all, let alone in a simple sentence. Finally, I was not satisfied with Needham's answer to his own question. He alluded to the importance of Christianity for the emergence of modern science, but his answer was mostly materialistic. On the contrary I held that Christianity played the pivotal role in the emergence of modern science. A basic assumption of modern science was that, behind the variety of phenomena there existed universal forces that controlled them. This universal behind-the-scene approach was much more associated with the Christian worldview than Chinese philosophy. The basis of Needham's answer and his proposal of the Needham question in the first place was his convergence theory, the belief that all the sciences of humanity converged to modern science. The convergence of technology was closer to truth, because technology to a large extent was accumulative. However, science was quite different. As a view of the outside world it's heavily dependent upon the general worldview of a culture. In this sense modern science was very Western indeed.

In my dissertation I handled a variety of issues. In this short essay I only want to highlight some key ideas. Brief explanation will follow the outline below:

- Humanism

- The human predicament

- The epistemological circle

- The immanent transcendence

- Organizational naturalism

- Organization as a separate dimension

- The organizational spectrum

- Incorporating materialistic naturalism and organic naturalism

- Elitist diversity

- Elitism

- Diversity

- Freedom as transcendence through cultivation

- Chinese modernity

- A synthesis between Chinese tradition and Western modernity

- The second revival

- Major hurdles

The following framework is about a synthesis between Chinese and Western thoughts. This grand synthesis also removes specific dichotomies on both sides.

Humanism

Humanism is the general outlook and basic principle. Generally speaking it puts humans in the center of the world and values humans the most. Theoretically it's a synthesis between Chinese humanism and humanism developed in Western modernity. Since the establishment of classical philosophy Chinese culture has been focused on human affairs. In Western modernization we also saw a general process of lifting the status of humans, starting with Renaissance.

The human predicament

Chinese philosophy was focused on human affairs. This unique humanism dominated the world outlook, according to which humans occupied the center of the world. The universe, heaven and earth, was even modelled after the human body. In this world everything is interconnected. Heaven was connected with earth. Humans were inseparable from nature. There were no distinct objects standing opposite to humans as subjects. This cultural monism determined that it's difficult for Chinese philosophy to realize the human predicament, because the boundary was in principle out of sight.

In the Christian world human life was just a transient stage while God occupied the center. Since the human world was not in focus, the genuine human predicament was also hard to reach. This had to wait till the modern period when the focus was shifted from God to humans. In philosophy the epistemological turn was revolutionary, because after the turn the human individual became the starting point of philosophical thinking. Descartes, the father of modern Western philosophy, began to construct our knowledge of the world from the thinking subject. Of course, at the beginning the help of God was still indispensable. Two conditions were essential to revealing the human predicament. On the one hand, the human world had to be in focus. On the other hand, the world beyond human world had to be in focus as well. These two conditions were met only in Western modernity.

Modern Western philosophy started with Cartesian dualism, so the tension between the human subject and the objective world became a basic theme. The Cartesian dualism was in fact the modern embodiment of the dichotomy between the human world and the world of God. And the tension was a reflection of the effort to shift the focus from God to humans and the resistance it encountered. Kant first reached the revelation of the human predicament. God had no place in Kritik der reinen Vernunft, because it belonged to the noumenal world, an unknown realm for humans. However, he kept a place for God in Kritik der praktischen Vernunft. So he held there were universal moral laws and they worked as undefiable duties for humans from above. Then Nietzsche proclaimed that "Gott ist tot" and we needed to revalue all the values. But for a culture that had lived under God for centuries it's just difficult to give up God completely. So God was transformed into the theory of everything and the human world was still regarded as a superficial phenomenon that could be reduced. On the other hand, the will to power found its most effective tool in modern technology. It's so powerful that a new fetish had been formed. At last, Heidegger offered a profound analysis of the human existence in Sein und Zeit. But facing the new God with its ever more discernible destruction he could only invoke the traditional God to save us.

Unfortunately humans have to take care of their own fate. That's the human predicament. Human consciousness is relegated by materialists as mere folk psychology that needs to be debunked just like the geocentric worldview. But actually it's the water that we have to float the ship of our knowledge of the whole world on. Every once in a while we had to remodel the ship somewhat to cope with new turbulences in the water. In that case we could only do it while the ship was still floating. There is no "solid" ground we may put our ship on. No, the shore is not reachable. In Rorty's terms there is no nature on one side and the mirror of nature on the other. On the contrary we create our own nature, as Kant claimed. Neither the traditional God nor the new God could save us. We have to learn to live on our own. In this context Chinese philosophy may come into play. If it's not capable of realizing the human predicament, it may help us move out of this modern predicament, or live happily in the human predicament. Anyways Chinese have been living successfully in the majority of time essentially without God. But before it could make any contribution it has to get out of the shadow of the impact of Western modernity first.

The epistemological circle

The epistemological circle is part of the human predicament. Epistemology is the theory of human knowledge. Basic epistemological questions are: What's the nature of human knowledge? Where does our knowledge come from? These are also the central questions of modern Western philosophy. We need to follow the milestones in its development in order to explain the idea of the epistemological circle.

- Descartes: innate knowledge, or knowledge as given

This was the starting point. Here knowledge was built into the thinking subject. Knowledge could be obtained from the thinking subject itself with good method. Basically for Descartes knowledge was something given to us that needed no explanation. - Kant: space and time, categories and principles as given

For Kant most part of human knowledge was not innate. But it couldn't come purely from outside the subject either, as the empiricists maintained. Space and time as transcendental form made sensation possible. On top of that perception and knowledge were made possible by some basic logical categories and principles. But space and time, those categories and principles were given to us with no explanation. - Heidegger: human existence as given

I see in Sein und Zeit an endeavor to explain space and time with human existence. Both were based on Sorge as the fundamental mode of human existence. For Heidegger space and time were no longer something given, but had their existential foundation. - Dreyfus: human body as given

By emphasizing the crucial role of human body, I would argue, Dreyfus pushed Heidegger's philosophy further and added another link. Now he put the human existence logically on top of the human body. We have such a body therefore we have such a form of existence. In particular we could explain Sorge with desires in the human body. - Closing the circle

An obvious next step is to explain the human body with natural history. The human body is the fruit of many years of natural evolution. However, after this we cannot go any further. We started with knowledge as given and end up with explaining our knowledge with our knowledge about natural history. In this way we've closed the epistemological circle. And this final circle we reached is the best thing we could have.

The immanent transcendence

Chinese philosophy couldn't realize the human predicament only because it took it for granted. Buddhism regarded human life as miserable suffering caused by insatiable desires and a phase in an endless cycling. Transcendence was achieved when one fled the endless cycling and obtained a timeless, eternal life. Christianity saw human life as a transient prelude in preparation for an eternal and happy life in the heaven. Transcendence was achieved when one successfully redeemed his/her sin and was judged to enter the heaven. In both cases transcendence lay beyond human life. In stark contrast transcendence in Chinese philosophy lay within human life. Hence the concept immanent transcendence. It took the form of the ideal of the sage. Transcendence beyond everyday life was an eager pursuit of Chinese philosophy. But the destination, sageness, was definitely a part of human life. In this way Chinese philosophy took a very positive attitude toward the human predicament.

The biggest confusion concerning Chinese culture was no other than the dichotomy between Confucianism and Taoism. According to the so-called dichotomy between chu shi and ru shi 出世入世之分 Confucianism was regarded merely as practical moral teachings while Taoism was mostly depicted as seclusionism and often aligned with Buddhism. But the fact was exactly the opposite. From Confucius to modern Confucianists the persistent ultimate pursuit of Confucianism had been an ideal that lay well beyond practical everyday life. Even the kingness without was subordinate to sageness within. On the other hand, the central concern of Taoism had been a happy human life, although it suggested a slightly different path to achieve that. Contrary to Buddhism Taoism valued human desires much. A happy human life had to be based on human desires, but it demanded a great amount of wisdom to reach the realm of xiao yao 逍遥之境. And xiao yao only existed in the human world. Feng was good at capturing the immanent transcendence in his theory of the spheres of living. Using his term the supermoral sphere was the ideal of both Confucianism and Taoism. There was no difference between them in this respect. On the other hand, their different emphases on the path to sageness provided a free space that allowed each Chinese intellect to strike their own balance between realism and idealism.

Realizing the human predicament may cast a gloomy view over the fate of humanity. But the immanent transcendence brings the light of hope. It's true that we humans are just limited existence, but in our limited human world there is still infinite space for each human individual to maneuver. Realizing the human predicament also brings the whole humanity closer. In the end we are essentially on the same boat and share the same fate. The day will finally come when the whole humanity will work together and be confident enough to act as their own masters.

Organizational Naturalism

Organizational naturalism is the ontology. But here ontology should be understood within the humanistic framework. In Kantian terms it's about the phenomenal rather than the noumenal world. In Heideggerian terms the meaning of being has to be sought in the existence of humans. Theoretically organizational naturalism is an extension of materialistic and organic naturalism and incorporates both in it. The former is the dominant ontology of Western modernity whereas the latter that of Chinese philosophy.

Organization as a separate dimension

1589, Pisa: In the legendary Leaning Tower experiment Galileo dropped two metal balls of different masses from the same height and they reached the ground at the same time. This experiment disproved Aristotle's theory of gravity, which stated that every object had its goal in the center of the Earth and heavier objects had a bigger tendency (higher speed) to reach their goal. This was a symbolic event. With some other events it marked the beginning of modern science.

1958, Shanghai: Doctors in Shanghai First People's Hospital successfully performed a tonsillectomy surgery with acupuncture anesthesia. Since then acupuncture has been more and more accepted in the modern world. Scientists have tried hard to provide a reasonable interpretation of the mechanism of acupuncture in terms of modern medicine, but without success.

Aristotle proposed four kinds of causes: the material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause and the final cause. Modern science kept the first and third causes and threw away the other two. Thus matter and force became the final building blocks of the modern scientific world. Accordingly mass and energy became the two fundamental measures. The reduction of the whole world to matter and force has been eagerly attempted. Unfortunately organism proves to be defiant and mind is even more recalcitrant. Organicism provided an alternative worldview to modern science. But Aristotle's organicism and that in Chinese philosophy had different flavors. Whereas the former was teleological the latter was holistic.

The development of science has reached a point where the basic assumptions of modern science need to be questioned. One of the assumptions was mechanism, according to which the world worked like a machine and could be broken into separate parts and studied independently. This was already challenged in the physics revolution a century ago. It highlighted process beside matter and to some extent brought Aristotle's formal cause back. Now it's time to bring back the final cause, but with a more comprehensive picture.

Besides matter and force, which have been step by step unified, we need to propose organization as a separate dimension of the world. Matter and force are measured with mass and energy, which have been shown to be mutually-convertible. However, the world is not just about mass and energy, but also how matter and force are organized. The measure of organization is complexity. An object such as the Sun may have huge mass and energy, but little complexity. On the contrary, another object such as the human brain may have little mass and energy, but astonishing complexity. Without organization as a separate dimension there is no easy way to explain this remarkable disparity.

The organizational spectrum

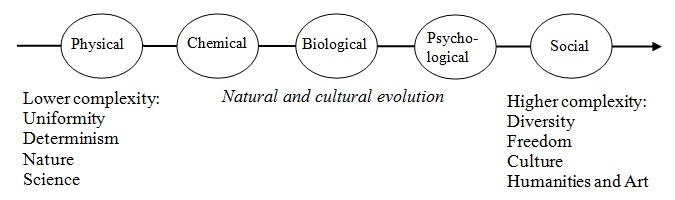

The organizational spectrum is a display of the world along the organizational dimension in order of complexity. The following diagram is taken from my dissertation (p. 143):

Here we have 5 major organizational levels arranged from left to right with ascending order of complexity, resulting from natural and cultural evolution. They are physical, chemical, biological, psychological and social levels. The corresponding entities are atoms and subatomic particles, molecules, life, mind and society. In terms of evolution there are only 4 stages. The universe started with the pure physical world. Then molecules were formed when it cooled down. Later life appeared under very rare circumstances. The last two entities are intertwined. They came into being at the same time and co-evolved. The state of mind without society only exists in some people's thought experiments.

Logically the 5 levels constitute a hierarchical system. On the one hand, levels of more complexity build on top of levels of less complexity. So all the physical and chemical laws are obeyed in a human body. And human mind is based on the human body, the whole body, not just the brain, to be precise. (The brain in a vat turns out to be another illusion.) On the other hand, every higher level with more complexity brings something new. Reductionism is a biased view of the hierarchical system. It only has half of the picture in sight. In particular, it sees the first kind of relationship among the levels, but oversees the second.

Incorporating materialistic naturalism and organic naturalism

With the organizational spectrum we could make better sense of the existing major world views:

- Supernaturalism Supernaturalism grasped the higher end of the organizational spectrum and projected it to the whole world. So the whole world was generated and controlled by certain spirit(s).

- Materialism Materialistic naturalism grasped the lower end of the organizational spectrum and projected it to the whole world. So the whole world could be reduced to matter and force, the physical world.

- Organicism Organic naturalism grasped the middle of the organizational spectrum and projected it to the whole world. So the whole world was interconnected like an organism and guided by some holistic principles.

It's clear now that they seemed to be from those blind men who were examining the elephant and making comments about it. All the views were biased and the picture is much richer. Yes, we have a world that contains more than one kind of entities. It's time to celebrate diversity and give up the notion of a theory of everything, no matter whether it takes the form of the scholastic philosophy, Hegel's system of the Weltgeist, or the contemporary Grand Unification Theory.

Elitist Diversity

Elitist diversity, or diverse elitism, is the basic principle concerning human individuals. Theoretically it's a synthesis between elitism and individualism. The former is the basic principle of Chinese traditional culture whereas the latter that of modernity. Elitist diversity is the opposite of egalitarian universalism, which I identify as the Western implementation of individualism. It's also a replacement for monotonic elitism, according to which there was only a single path toward excellence in traditional China.

Elitism

Elitism is the opposite of egalitarianism. Whereas the latter holds that human individuals are equal the former maintains that they are not equal. However, both views are hollow without qualification of the notion of equality. For instance, the statement that all men are created equal is only valid in a very abstract sense. Parents and teachers know well that children are not created equal. Human individuals vary in many respects when they are born and grow to maturity. That constitutes the foundation of their fate in adult life. Major factors may be listed below:

- Genetic traits No two persons share the same whole set of genetic traits, except identical twins. But they are critical determining factors. Many human talents come from their genes.

- Pregnancy conditions Although a child is born ten months later, the life journey starts with pregnancy. This stage is no less important than the next one.

- Infant and child care In this stage both the child's body and mind develop in a specific physical environment, rather than the relatively homogeneous one in the last stage.

- Education The child's body continues to grow in this stage, but education mainly involves the development of the child's mind (cognitive, emotional, moral abilities and knowledge) in a specific cultural environment.

With so many complicated factors, even identical twins soon diverge in their life journey.

Some reasonable criteria of inequality in the traditional society turn out to be invalid in a modern society. The son of a nobleman became a nobleman by birth. From the individualist point of view this appears to be unfair, because birth in terms of social status is arbitrary for the individual. Similarly other personal features such as age, sex, race and faith also gradually lost their ground as valid criteria of social inequality. Now the question is, what is the limit? What can we still keep as valid personal features for determining social relationship? In the extreme case of Rawls's "veil of ignorance" everything is stripped off, except the basic rational ability to do max-min calculation, which is a necessary functional element in his thought experiment. In this way human individuals degrade into the most abstract entities, at most in the sense of members of the species homo sapiens. It seems that, if we go too far human individuals would disappear just like in the traditional society.

Elitism based on merit becomes more meaningful in this context. Merit can be roughly defined as existing achievements and the qualities to achieve more. That's what it takes to be essential to a human individual. Physical and spiritual talents are crucial to achievements, but personal efforts are as important as talents. According to Rawls's principles a great singer is not justified for a better life than an ordinary person because he/she happens to be endowed with an attractive voice. That talent has to be put behind the veil of ignorance, to be fair. In contrast merit elitism holds that talents are essential parts of an individual. Inequality based on talents is not only justified, but it also should be emphasized. This may be achieved in two steps. First, each child should be given equal opportunity to develop their talents. Providing subsidies for child birth and care is one possible policy. But more importantly each child should be given equal opportunity of education. Second, each adult should be given equal opportunity to apply their merits. Meritocracy, with the principle that meritorious people should rule a society, is implied by this second principle. Generally we can see, merit elitism only goes against abstract egalitarianism, but is committed to a good set of egalitarian principles at the same time.

Diversity

Having qualified elitism with merit, now we need further to qualify merit itself. What can be called achievement? What can be counted as greater achievement? Sheer economic wealth or political power is not an indication of achievement. Even one wins a lottery of billions we don't think he has made a great achievement. Neither do we do the same thing to a king who inherits a kingdom. Achievement has to involve a meaningful challenge that demands both talents and efforts. The more talents and efforts it demands the greater the achievement. Meaningful doesn't have to be useful. In fact, material well-being is just the basic challenge for human beings. The most meaningful challenges for human body and soul are all beyond utility. Scaling Mount Everest has little utility, but successfully doing it brings utmost sense of achievement. Philosophy and art are the least useful endeavors, but they display the Mount Everest of human spirit. Elitism so qualified is in good harmony with organizational naturalism because it values complex human life. And complexity implies diversity.

Neither elitism nor individualism alone could guarantee diversity. In traditional China elitism was practiced in the form of meritocracy. Government positions from ministers downward were filled by people selected with a sophisticated examination system 科举制度. The subject of the examination was even focused on humanities. And the system allowed a large degree of social mobility rarely seen in other places. It's normal for a talented and capable person to be lifted from the bottom of society to the top in a short period of time. However, the authoritarian principles didn't permit a significant range of diversity. And going through the examination system was the only path toward excellence. So it's not unusual that many people were still preparing for the examination in their 40s, or even 50s.

Individualism was developed in Western modernity, but under the universal principles even the diversity that survived in the traditional society had been wiped out. Modern science in principle promoted universality and downgraded uniqueness. Evidences had to be universally and empirically verifiable. This positivist thinking had dominated and permeated the modern spiritual world. Any thought that didn't conform to the universal principle was regarded as backward. The globalized capitalist economy is unifying people's material life on this planet. People everywhere are now visiting the same stores, using the same brands. And finally democracy is considered as the universal political system and spread to the world, without realizing that its smooth and effective functioning requires some strict preconditions.

Freedom as transcendence through cultivation

Human individuals were liberated from the traditional authoritarian society in Western modernity, but they were subjected to universal principles. These new restrictions were more hidden than the old ones. When celebrating their liberation they had more difficulty to feel the burden of their new chains. Dissenting voices were not nonexistent. Tension between Enlightenment and Romanticism, scientism and humanism had been persistent. But the former end of the tension had been overwhelmingly dominant.

In this context liberty was understood as freedom from all kinds of authority and finally based on abstract personal will. So a person was free if he/she could do things at will, as long as he/she didn't interfere others to do the same. In particular, freedom of speech has even degraded into speaking whatever one wants in this internet age. However, speech is supposed to convey meaning and its weight is attached to responsibility. When speech is separated from responsibility and loses meaning it becomes hollow voice or text. And personal will is apparently not a fundamental entity. People with different levels of knowledge and vision will differently in quality. Therefore, freedom based on abstract personal will is just superficial liberty. To make it authentic personal will has to be substantiated with qualities that are associated with genuine freedom. There are different spheres of living. Freedom is obtained as one transcends the current sphere through personal cultivation. And that demands both talents and efforts.

Just like organizational naturalism combines materialistic and organic naturalism and transcends both, elitist diversity combines universal individualism and monotonic elitism and transcends both as well.

Chinese Modernity

Under the impact of Western modernity Chinese culture has been undergoing a new fundamental adaptation process. It has not moved out of the shadow of the impact yet. A new synthesis is needed, which requires fundamental deconstruction of both sides. Without clear identification of both Chineseness and modernity we could only have superficial solutions, no matter whether it's 中体西用 or 西体中用. This calls for the second revival of Chinese culture, which essentially will be reasserting cultural identity through assimilation and adaptation. The first revival was reaction to the impact of Buddhism whereas the second will be one to the impact of Christianity.

A synthesis between Chinese tradition and Western modernity

As the term "Chinese modernity" suggests, it excludes two stances by definition. One is to hold onto Chinese tradition completely and the other is to pursue full-scale Westernization. Chinese modernity has to be certain form of combination of Chineseness and modernity, essentially a synthesis between Chinese tradition and Western modernity. Three major tasks are involved in this synthesis:

- First, we need to pick the right elements from Chinese tradition. These have to be essential features of Chinese culture. They are what make Chinese culture Chinese, but not traditionally Chinese.

- Second, we need to pick the right elements from Western modernity. These have to be essential features of modernity. They are what make a society modern, but not Western.

- Third, we must combine all the elements from both sides into an organic whole. The combination we make cannot be just a mixture of various elements.

Imagine the spectrum of light. If we compare Chinese tradition and Western modernity to the infra-red and ultra-violet segments respectively, then we have a spectrum of possible forms of combination in between. What occupy the two ends of the "visible" spectrum are 中体西用 and 西体中用 respectively:

- 中体西用 Zhang Zhidong's proposal: Keep the traditional ethics and social structure while embracing modern technology and industrialization.

- 西体中用 Li Zehou's proposal: Adopt further modern Western principles and social structure (social public ethics 社会性公德) while keeping traditional Chinese ethics as "lubricant" (religious private ethics 宗教性私德).

As can be seen, my own proposal lies in the middle of the spectrum. To me modernity is not just modern technology and industrialization and on the other hand Chinese tradition should play a role much more than just a lubricant.

The second revival

Now we put Chinese modernity in the history of Chinese thought. Along with Li I believe there are four major phases in Chinese history of thought:

- The classical philosophy This happened during disintegration of the primitive society. The classical philosophy was established through sublimational metamorphosis of shamanism.

- The new system This accompanied the establishment of new social order in the Han dynasty. The system of Yin-Yang and five elements was a synthesis of the pre-Qin schools and resonated well with the new social order.

- Coping with the impact of Buddhism Buddhism was introduced to China via the Silk Road in late Han, but it was widely spread only after Han. In that period Chinese society was in disarray and Confucianism lost its dominance. The influence of Buddhism in China reached its peak in the Tang dynasty. However, in late Tang scholars started to criticize Buddhism vehemently. This was the beginning of the first revival of Chinese thought. In Song, Ming and Qing Confucianism regained its dominance.

- Coping with the impact of Western modernity (Christianity) Christianity in China dated back to the Tang dynasty, but its big impact only came with Western modernity in the last two centuries. Compared with Buddhism the impact of Western modernity took effect more dramatically. It has revolutionized Chinese society in about a century. In the meantime the traditional social order was toppled. For the moment China still lies in the shadow of the impact. The second revival is still a cause that needs to be fought for.

The first revival will definitely provide insights for the second. A revival is the reassertion of cultural identity in a new context, with the following two basic strategies:

- Assimilation 同化 This is the process of transforming a foreign object/feature into something that fits in the local system. Zenism is a typical example of assimilation in the first revival. In Zenism Buddhism was brought in the framework of Chinese cultural monism. So a basic Zenistic teaching was that Buddhaness 佛性 existed in everyday life and in order to reach it one didn't need to go to the temple and give up human desires. Buddhaness was typically revealed in a sudden enlightenment 顿悟 in the course of ordinary daily life.

- Adaptation 应变 This is the process of transforming a local object/feature according to foreign principles. In the Song-Ming philosophy, no matter whether it's the Li philosophy or the mind philosophy, the prints of Buddhism were obvious. For one thing, the dichotomy between the heavenly Li and human desires 天理人欲之辨 was apparently an idea that conformed to the Buddhistic principles and was very foreign to, or even contradicted Chinese classical philosophy.

We can imagine the second revival of Chinese culture will have similar look, although we're now facing the impact of a major human culture farther west.

Major hurdles

With a deeper reflection on Chinese modernization process and a careful assessment of the current status of China one could easily reach the conclusion that Chinese culture still lies in the shadow of the great impact of Western modernity. On the road leading toward the second revival there are still major hurdles we need to jump over:

- The illusion of Western modernity The illusion of Western modernity was a result of its great impact and the huge humiliation that came with the impact. The series of conflicts between the weakened Qing Empire and the industrialized West put Chinese and Western cultures side by side in stark contrast. The notion of backwardness of the former and superiority of the latter constituted an essential part of the humiliation complex. Therefore in the New Culture Movement Mr. S 赛先生 and Mr. D 德先生 were worshipped as the gods who could save China. Unfortunately a century later this is still the dominant view.

- The illusion of Chinese tradition The illusion of Chinese tradition was partly also a result of the impact of Western modernity. This mainly took the form of cultural self-denial. But it was also in large part a result of the impact of Buddhism. This took the form of cultural confusion. Therefore Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism 儒道释 were often listed as the three pillars of Chinese culture and Taoism was usually aligned with Buddhism. With this confusion a clear identification of Chineseness will be difficult to reach, even after we regain cultural confidence generally.

- The specific assimilation and adaptation And finally we have the most challenging task to figure out what the specific assimilation and adaptation should look like. A clear identification of both Chineseness and modernity will constitute a solid base, but there is still a great amount of work on top of that.

Personally I have managed to generally jump over the first two hurdles in 30 years. Now I am standing excitedly and eagerly in front of the third one in awe.

It's a huge project to substantiate the above framework. The grand project has to be tackled piece by piece. The following two projects are extensions of chapters of my dissertation. In the first project I will explore more details about technology. The second project requires a systematic study of Chinese classics. My plan is to grow them into separate books.